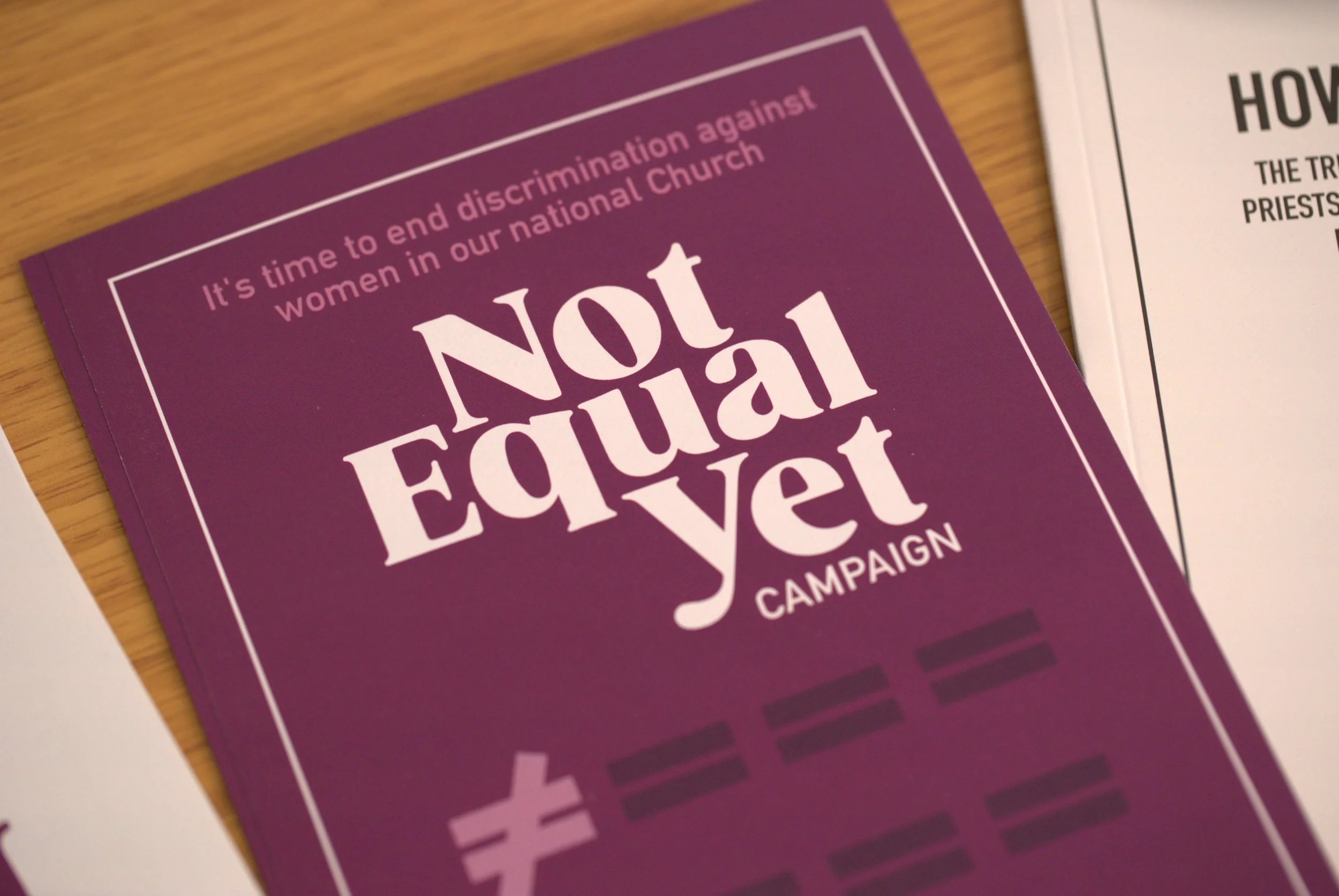

Posing a Problem: Not Equal Yet

Published originally on ViaMedia.News

“When you expose a problem, you pose a problem.” So writes Sara Ahmed in her book Living a Feminist Life. Ahmed is talking about that phenomenon, well known to many of us, by which the person who names a problem within an institution, group or culture, becomes seen as the source of the problem. It happens to black people exposing racism, to women exposing misogyny, to disabled people exposing ablism, to LGBTQ+ people exposing homophobia and transphobia, indeed to any person naming a dynamic to which the institution would prefer to remain oblivious.

It happens to women when we expose misogyny and sexism in all sorts of places: in the academy, which is Ahmed’s context, in the workplace, in our communities, our families and, yes, in our churches. It is so much easier to say that the problem is these uppity women who won’t shut up and be grateful for what they’ve got, rather than to confront the underlying and persistent inequalities which they are naming. (“Easier for whom?” we might ask.)

To say, 30 years on from the ordination of the first women as priests in the Church of England, that women are still not equal yet in the church is to expose a problem. But it is also to state a fact. The statistics back it up: in the most recently available set of ministry statistics, just 33% of stipendiary clergy are women, and women continue to be under-represented in senior roles, with just 7 women out of 42 diocesan bishops. Women’s experiences back it up too, though that hard-won knowledge and wisdom is rarely afforded the respect or consideration it is due.

Indeed, that women in the Church of England are not equal yet is enshrined in the legislation of the church, in the form of the House of Bishops Declaration on the Ministry of Bishops and Priests (GS Misc 1076) which, among other things, introduced the Five Guiding Principles. There are churches in which women are prohibited from presiding at the altar. There are no churches in which men are prohibited from presiding at the altar. We are not equal yet.

But to say that, to state that women are not equal yet (in this and so many other ways) will always attract a hostile response. Why can’t we just be grateful for what we’ve got? Why do we have to make everything about gender? What about the feelings of those who can’t or won’t accept our ministry? Why can’t we just be kind?

This is exactly the sort of response Sara Ahmed predicts: “When you expose a problem, you pose a problem. It might then be assumed that the problem would go away if you would just stop talking about it, or if you went away.” But of course, that is not true. If we never spoke about it, the problem would still remain. But those who are unaffected by the problem would be allowed to preserve the privilege of their obliviousness. They would not be confronted with the problem. The problem would persist, but the burden would be carried only by those who do not have the luxury of being able to choose to ignore it: in this case, women.

So we must speak. We must say what we know to be true. Women are not equal yet in the Church of England.

And we must say other things we know to be true too. Women are made, equally with men, in the image of God. The subjugation of women is not the will of God. The body of Christ is damaged when women are not able to exercise their God-given gifts and vocations. The fact that women are not equal yet is not just a problem for women, but for the whole church. And it is not only an ethical problem, but also a theological and ecclesiological one.

Women are not equal yet. And that is a problem. Like any problem, it will not be solved by being hidden away. It can only be addressed by being brought into the light, spoken about openly and without fear. The Not Equal Yet conference organised by WATCH, aims to do just that: to state openly that women are not equal yet. And to ask what we, as a church, are going to do about it.

We have to be able to have that conversation, however difficult or painful it might be. To expose a problem is to pose a problem. But I would rather pose a problem, than persist in the lie of pretending that there is no problem here to be exposed.

It is obvious already from conversations online and offline that even to have the conversation, even to state the truth that women in the Church of England are not equal yet, evokes angry and defensive responses from some. That should not deter us. As Jesus said: “You will know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” And as Gloria Steinem said: “The truth will set you free. But first, it will piss you off.”

Exposing the truth of women’s inequality in the church is a vital step toward ending that inequality. And a church in which women and men are equal, a church which reflects the equality of people of all genders in God’s sight, is good and liberating news for all.

To expose a problem, to pose a problem, is hard. It is hard to make ourselves so exposed by admitting the truth: that we are not equal yet. The naming of truth is hard and holy work. And it is necessary work, in order to live ever more fully in the way of Jesus, who was never afraid to name the hard and exposing truths of injustice, and in order to bring God’s church ever closer to embodying the justice of God’s kingdom.